from Queen’s Quarterly- 1905

If Richmond had had a newspaper in 1904, a headline might have proclaimed, “ Montreal Millionaire Philanthropist finances Richmond School Garden”. Indeed it would have been valid because Sir Charles Macdonald, owner of a multimillion-dollar tobacco empire, did indeed provide funds for a three-year project that placed Richmond on the leading edge of a movement to radically change the nature of Ontario education. Why did he sponsor a garden in Richmond and what was it like?

The Initiators

In the spring of 1904, Ontario, along with Quebec and the maritime provinces, became part of the Macdonald School Garden project. In Ontario the pilot program was introduced in Carleton County. In addition to the villages of Galetta, Carp, North Gower, and Bowesville, Richmond became the site of an educational experiment. Financed by the millionaire tobacconist Sir William C. Macdonald, and following principles developed by Professor James W. Robertson, director of the Macdonald Rural Schools Fund, Richmond became the site of a three acre school garden aimed at shifting the focus of rural education.

Sir William, the philanthropist who financed massive building projects at McGill University and Guelph’s Ontario Agricultural College, believed that rural life must be ennobled and scientifically improved to preserve its idealized values and to slow the exodus of young people to the morally risky cities.

The director of his project, Professor James W. Robertson, was the federal government’s first commissioner of agriculture and dairying, as well as first principal of Macdonald College.

Two local men, Robert H. Cowley, Inspector of Schools, and John W. Gibson, an itinerant teacher, were directly responsible for the gardens in Carleton County. Robert Cowley wrote an article (much quoted in this blog) espousing the virtues of the program. John Gibson visited each garden one day a week, directed the garden work, gave lessons in practical aspects of nature study and connected the practical aspects of gardening with ordinary school work (for example measurement/arithmetic).

The Rationale

Before 1900, Ontario schools, both rural and urban, concentrated on the teaching of “academic” subjects: primarily languages, sciences, mathematics, and history. By the turn of the century a progressive movement called for the introduction of new vocational curricula including the study of “manual training”, home economics, nature studies and agriculture. School gardens were part of this movement; students were provided with the opportunity to move outside the classroom and study agriculture and nature. According to the designers, students would become well-rounded children who would develop values such as responsibility and thriftiness, and modern, scientific skills such as observation, the linkage of cause and effect, and analysis of data.

The Gardens

from Queen’s Quarterly-1905

Most of what we know about the school gardens comes from an article written by Robert Cowley and published in the Queen’s Quarterly in 1905.

The Macdonald Fund established a highly structured program and paid for all aspects of creating and maintaining the school gardens: land acquisition (if additional land was necessary the fund paid half the cost), training of supervisors and teachers, planning, fencing, seeds, and tools. Supervisory teachers such as Mr. Gibson were sent to American universities to learn the philosophy and strategies behind the program and his salary was paid by the Fund for three years. The Macdonald fund gave an initial one hundred dollar grant (and additional yearly grants) to each school section when teachers were sent to Guelph for training.

from Queen’s Quarterly

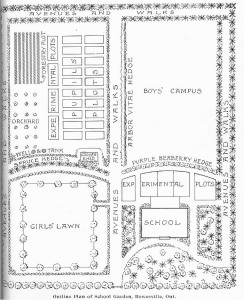

In Carleton County, each garden covered two acres, including the school, except for Richmond’s garden that covered three acres. We don’t have the specific plan for the Richmond garden, but we know it was similar to this at Bowesville (5 miles south of Ottawa).

There was to be a belt of ornamental native trees and shrubs surrounding the grounds and bordering walks. A “playground” of about one-half acre was to be “set aside” for the boys while the girls were given a quarter acre “lawn” surrounded by shade trees.

The garden was to include a “forest” in which “the most important Canadian trees” would be grown from seed and by transplanting. Senior boys were taught grafting. There was also to be an orchard and a plot for cultivating “the wild herbs, vines and shrubs of the district”. Part of the garden was to include an attractive approach to the school, “including open lawn, large flowering plants, foliage, rockery, ornamental shrubs &c”.

An important part of the garden was the shed that on average cost $75 to build. The program provided each student with the required tools and the shed was organized to ensure that students cleaned, maintained and stored their tools properly. Part of the shed also acted as a small green house.

from Queen’s Quarterly – 1905

There were two types of plots – experimental and individual. The experimental plots were usually larger than the individual (from 200 to 2000 square feet) and were used for teaching agricultural skills: crop rotation, value of fertilizers, effects of “spraying”, selection of seeds, merits of soils, and productiveness and quality of different varieties of crops. Cowley tells us that each school studied particular crops and he gives several examples but doesn’t tell us if any of his examples applied to Richmond. He says that one school studied corn, clover, tomatoes, and cabbage; another beans, peas, beets and potatoes; while a third pumpkins, squash, cabbage and cauliflower. He says that “At all the gardens special plots will be devoted to small fruits such as strawberries, raspberries, gooseberries, and currants.”

The students were also given plots which were solely their own. Cowley tells us that these had the dual purpose of developing agricultural skills as well as personal skills. The plots varied in size from 72 square feet to 120 square feet depending on the student’s age or strength. Each student grew both vegetables and flowers either in the same plot or in two different ones.

Cowley tells us “About twenty varieties of flowers were grown at the different school sites.” Among the most popular were “aster, balsam, mignonette, nasturtium, pansy, petunia, phlox, sweet peas, and zinnias”. The plots included a variety of vegetables and cereals “ beets, cabbage, lettuce, potatoes, radish, tomatoes, barley, beans, clover, oats, and wheat.”

from Richmond “150”

Community Reaction

We know from Cowley’s writing that he hoped the community would embrace the new gardens. He tells us, “The garden in Richmond is within a short distance of the grounds of the County Agricultural Society, and will annually be open to the inspection of many hundred visitors to the fair”. (In 1905, Richmond School was located on Cockburn St. near Martin St.) He goes on to say that the gardens in Carleton have already attracted “much local attention” and that “last autumn the products of the gardens won about a hundred dollars in prizes, given both by the agricultural societies and by private citizens”.

There is no doubt that locals were impressed, at least initially, by the experiment. Each garden was owned by the local school corporation and conducted under the authority of the school trustees.

The local newspaper, The Carp Review, seems to have fully supported the program and gave it much publicity. On July 7, 1904, The Review, in its “Richmond News” section announced, “ On Tuesday, Professor Robinson and Mr. J. W. Gibson visited the school garden. Part of the day was spent in the garden where Prof. Robertson instructed the children about their work. They then proceeded to the woods in search of flowers and later had tea”.

On April 13, 1905, , The Review reprinted an article from the Ottawa Free Press entitled “Nature Study Work”. It stated that J.W. Gibson, Superintendent of the Macdonald Nature Study Work, had left (Ottawa) for Carp and Galetta to supervise the spring work in the gardens there and that he would go on to Richmond and North Gower. The article pointed out “This is the second year of the work and much better results are expected than last year although the work then was very successful”. The positive review continued in the May 11th edition, “The children of the public school (Carp) have commenced operations in the garden and have quite a portion of it seeded already. A number of ornamental shrubs and trees have been planted this spring and everything points to a very successful year in this interesting and instructive work.”

Educators were also impressed with the gardens. They were the main topic of the 1905 Convention of the teachers of Eastern Ontario and similar gardens were introduced across the country.

Update: 31/01/2013 Many thanks to local historians/horticulturalists, Lee Boltwood and Joan Darby who pointed out the article in “A History of Canadian Gardening” by Carol Martin, Toronto: McArthur & Co., 2000. Martin states that the results of the gardens were impressive as the young gardeners were more likely to stay in school, and achieve higher marks overall on the standard high school entrance exams, than their peers in schools with no gardens. She quotes from Herbert F. Sherwood. Children of the Land: the story of the Macdonald movement in Canada. 1910., “In 1906, in Carleton County, in schools without gardens 49 per cent of the candidates passed, while those who came from the five schools to which were attached gardens 71 per cent were successful”.

Questions

Two main questions remain unanswered.

in Richmond School garden

from Richmond “150”

What did the students really think of the program? We are told that some students loved it and were willing workers both after school and during the summer vacation. However to date we have uncovered no student responses.

Did the program in Richmond continue after the three-year pilot project? If so, in what format? Since the Richmond school was burned in 1924 and the new Continuation school was built several blocks away on McBean St., there is no physical evidence of the garden. With teacher turnover and the problems of maintaining the garden in the summer, its longevity is unknown. We will update as new information is acquired.

Sources:

- The Carp Review.

- Cowley, R. H. “The Macdonald School Gardens”. Queen’s Quarterly. Spring 1905, 392-418.

- The Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

- Graham, Mildred et al. Richmond “150” Yesterday and Today 1818-1968. Ottawa:1968.

- Jones, David C. “We cannot allow it to be run by those who do not understand education” – Agricultural Schooling in the Twenties”. BC Studies . no. 39, Autumn 1978