To honour Richmond’s 200th anniversary, we will be posting factoids about our rich history. Over the next year you should expect to see 200 pieces of information that you may or may not have already known. The topics included in this post are: #21. Malaria #22. Main Street #23. Saw Mill #24. School #25. Interesting items ordered by George Lyon

If you have a question about the source of a factoid please contact us.

Factoid #21. Malaria. A disease we seldom associate with Eastern Ontario was indeed prevalent during the 1820’s. Sometimes called swamp fever people believed it was caused by bad air. Little did they know that it was a parasite carried by the mosquito. During the building of the Rideau Canal, 1827-1831, hundreds of workers and their families contracted malaria and many died.

Factoid #21. Malaria. A disease we seldom associate with Eastern Ontario was indeed prevalent during the 1820’s. Sometimes called swamp fever people believed it was caused by bad air. Little did they know that it was a parasite carried by the mosquito. During the building of the Rideau Canal, 1827-1831, hundreds of workers and their families contracted malaria and many died.

George Lyon was well aware of the problem and in July 1827 he ordered 2 lbs. of “Peruvian Bark” from his Montreal suppliers. Peruvian Bark was another name for cinchona bark, which had been used as a treatment for malaria for centuries.

At the same time Lyon ordered 1/4 oz. of quinine. This put the village on the leading edge of the treatment of malaria as French scientists had only isolated this new remedy in 1820. There was a great difference in price. Lyon paid a little more than three and one half shillings per pound for the bark but paid twelve shillings and 8 pence for the quarter ounce of quinine. He placed another slightly larger order in January 1829. Rare, expensive, and difficult to acquire, quinine was an unusual purchase in Lyon’s invoice book.

For whom did Lyon purchase the quinine? Settlers? Wealthy merchants supplying goods for the canal? We have no idea.

Factoid #22.

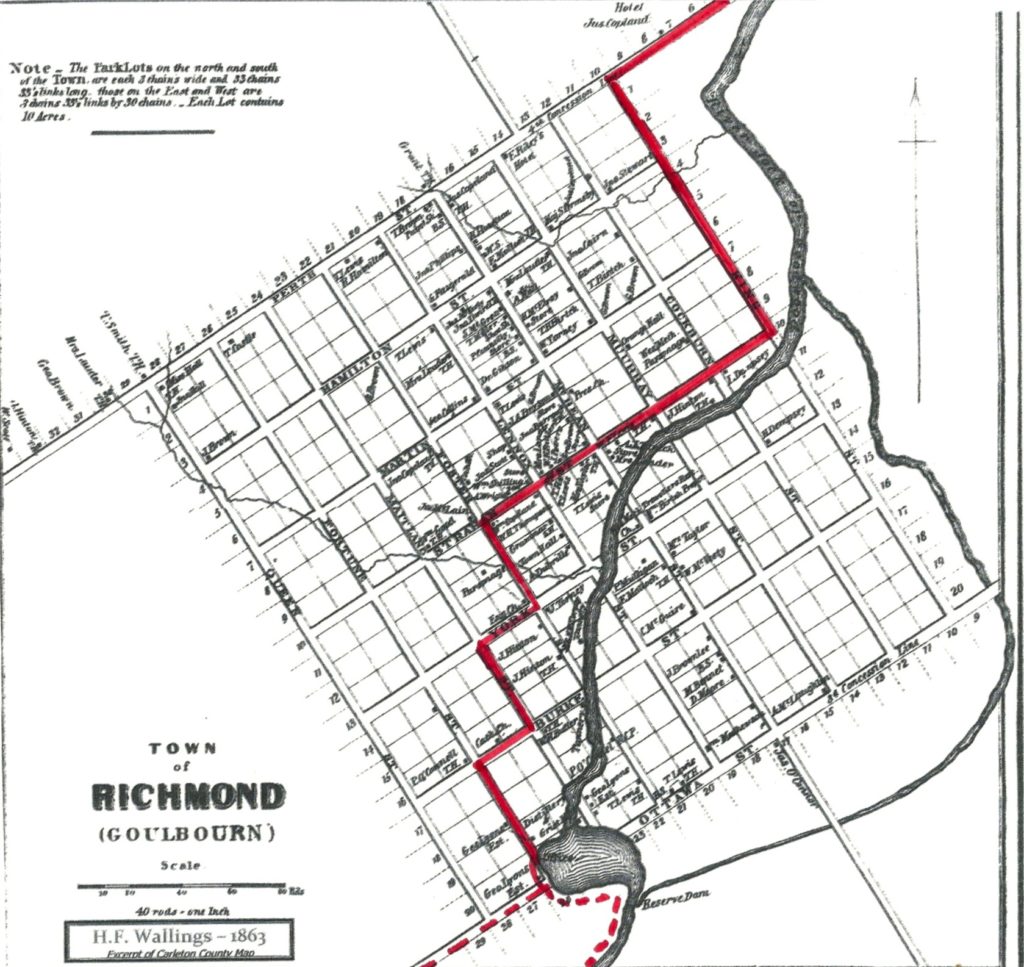

Today when we think of Richmond’s main street there is some debate whether it is Perth or McBean. All indications are that in the 1820s it was Strachan St. The following description is based less on fact and more on supposition. An analysis of the pattern of land ownership and distribution of buildings seems to indicate that Strachan was a well-developed area.

Coming from present day Ottawa, the road probably entered the village along Perth St. It likely turned south almost immediately onto King St. (or possibly Cockburn St). Two village dignitaries, Andrew Lett and George T. Burke owned park lots here. The block bordered by King, Strachan, Cockburn, and (Colonel) Murray St. held all the important official sites in the village. Here was located the depot where settlers collected their tools and rations. Beside it was the administration building which seems to have been used as an officers’ barracks as well as Col. Burke’s office. Burke was also the postmaster. On the same block was the school house, which was used not only as a school, but at least until 1825 by every religion denomination. Even into the 1830s it was used by Rev. William Bell of Perth when he came to preach in the village.

From the corner of Cockburn St. and Strachan St. the road probably continued along Strachan to Fowler St. The area along Strachan was well developed and contained the hotel of Maria & Andrew Hill. Both Capt. Lewis and Edward Malloch owned land along this route and possibly had their stores there.

The road continued past St. John’s Anglican Church (begun in 1823) and St. Philip’s (started in 1825).

West of St. Philip’s the route would have followed Fortune St. past George Lyon’s industrial complex: sawmill, gristmill, and distillery. There is no indication of the exact location of Lyon’s first store but he owned land at various points along this route.

The big obstacle to the west of the village was the swamp. To cross this area, the road followed Ottawa St. and/or hugged the river and the edge of the drowned land. Passing the carding mill, it entered the swamp just past the Joy Rd. between Ottawa St. and the Jock River.

Factoid #23. Trees. Richmond had ready access to wooden construction material. The

The first shanties or traditional houses built in 1818-1819 were made from either round or squared logs and lumber was often not required.

In 1821, George Lyon opened his sawmill and things began to change. An order from Captain Lewis and Lieutenant Horrie, in June 1821, shows the type of pieces produced: 500 pieces clapboarding (7 or 8 feet wide) and 300 pieces of plank (10 or 12 feet long and 12 to 20 feet wide). As well the order included other pieces: 2 – 35′ scantling, 18 – 15′ rafters, 46 – 14′ joists, 1- 48′ ridge pole, plates, bearers, posts, and other items. Even shingles were available as written at the bottom of the form were the words “Ten Thousand shingles”.

Lyon was also sending lumber outside the settlement. A notation in his Invoice book on June 1 1824 shows that he was rafting planks down the Jock and Rideau Rivers.

“Delivered to William Hobbs the under mentioned quantity of Deal Plank, Twelve hundred Pieces of Eleven Inch Stuff And Five hundred and Ninety four Nine Inch Ditto, the whole to be delivered in a safe condition at the Rideau Falls,…The above not delivered owing to ditto not being Properly rafted, now Lying at Half Moon Bay.” ( this would have been Half Moon Bay on the Jock)

After Lyon’s death in 1851, his estate was put up for sale. An advertisement in “The British Colonist” described the mill. “The Saw Mill which is built partly of stone and partly frame, contains one Upright Saw, capable of cutting three thousand of stuff in twenty-four hours; a thirty-six inch Circular, quite new and newly fitted up; there is plenty of spare room for putting up other machinery.”

An industry had been established.

Factoid #24. The military promised the soldiers coming to Richmond that they would have a school for their children. A schoolhouse was built on the administration lands and a teacher recruited. In 1821, Mr. Read arrived in the community and the next year he was replaced by Mr. Enough (Eynough). Each man received £50 for his services.

In July 1822, George Lyon purchased 4 dozen spelling books for a total cost of £2/14/0. This purchase gives the impression that a fairly large number of families were availing themselves of the educational opportunities. There is no indication as to whether or not girls were part of this number, nor is there any information as to whether the sons of all the settlers were being educated.

In Dec. 1822, the government stopped all funding, there was no money for a teacher, and the school closed. Harry Walker in “Carleton Saga” says that Stephen Eynough went on to run an independent school. He boarded around the Settlement, and also charged a modest fee. The family which hosted him became the site of the school while he lived at that location.

As in the rest of Upper Canada at the time, education became a private matter. As well as Eynough’s mobile school, those members of the community with literacy and numeracy skills could teacher their own children. A very few families might have hired a private tutor. Some families sent their boys to board outside the village; this was necessary for boys wanting the equivalent of our high school.

In February 1825, Lyon placed another order for teaching supplies: 3 Murray grammars, 3 Murray readers, 1 Joyce arithmetic, 1 Eason’s Latin Grammar and 2 Comic Song Books. This looks as if it may have been a special order for one family.

On August 7 1829, Lyon placed a large order with his supplier. It seems as if some effort was being made to reestablish a school or at least provide instructional material for a number of children. The order consisted of the following: 2 doz. Singles Universal, 14 copies Chili’s New Play Thing, 2 doz. Reading Made Easy, 2 doz. Child’s Instructor, 2 doz. Improved Primer, 2 doz. Histories Coloured Plates.

What we do know is that the sons of the officers and wealthy merchants were well educated and became lawyers, doctors and merchants. As to the children of the other settlers in the village we don’t know if they were literate.

Factoid #25. While Lyon was providing the basic products needed for the establishing of farms and businesses, he was also buying more expensive items. Which ones were for his own personal use, which were to stock his store, and which were to fill special orders is not clear.

In 1822 -1823, Lyon purchased 3 pieces of military grey cloth. At this time he and the other officers in the Settlement were setting up the First Carleton Militia. As they were all officers in the militia it is possible that this was material for at least part of their uniforms.

Lyon provided various items of clothing. The ones, which caught my attention were beaver hats (sold on commission for Eli Hurd of Burritt’s Rapids), scarlet stockings, “women’s fine Russia leather double soled shoes”, and a grey bear muff and tippet (stole).

In the early years, Lyon bought thousands of yards of material in a variety of price ranges. The most expensive was something called “Hunt Blue cloth” which cost more than £10 for 20 yards. The same type of material seems to have been available in brown and bronze. Silk material for handkerchiefs was purchased every year while “Navachino Chintz” appeared on the invoices in the latter years. As time went on ready-made items: trousers, frocks, and shawls appear on the lists more frequently. By 1829 the number and size of the orders for material became smaller but more specific. (It also seems that Lyon was more frequently asked to pay in cash) Rather than “pink callico” or “striped” cloth, the choices were designated by place of origin or descriptors such as “Super London Smocked Olive”.

Lyon imported some luxury food items. In July 1823, he bought a keg containing 4 doz. lemons, 4 doz. oranges and 14 lbs. of almonds. In November of the next year he was buying a barrel, which contained oysters, currants, rice and apples. Traditionally Lyon stocked tea but for the first time in 1824 he added coffee to his order.

As horses became more prevalent in the Richmond Settlement, Lyon stocked the appropriate supplies: 1/2 doz. curry combs and mane combs, and a horse collar. In July 1824 he bought a set of harness, a bridle and a whip. £5 was spent on a “ladies saddle” in 1826.

We see other items which were one time purchases: an umbrella, a gold broach, 3 table clothes, ivory combs, 21 issues of “Life in Paris”, 1 doz. pocket bibles, 1 doz. Highlander playing cards, and 11 pair of spectacles. Lyon had always purchased plates and other table settings in various price ranges, (see a previous post “George Lyon and the Montreal China Merchants”) and in 1829 he added 4 doz. tumblers, 5 doz. wine glasses, 2 doz. decanters, and 4 covered dishes. Lyon used the services of Nelson Walker, Silversmith and watchmaker. The firm not only mended watches and mounted broaches, but also, in 1824, provided 2 pairs Hull Pattern Salt Spoons.

One could literally order any product one could afford.

6 Responses to Richmond 200 – Factoids #21 – #25