Examining the Invoices of George Lyon`s Store

Purchased in large amounts

courtesy

UCLA-Spices as Meds

In today’s world of modern medicine, we take for granted that a quick trip to the doctor’s office will cure our illnesses. However, things were quite different in the early 1800s. Settlers were susceptible to the normal aches and pains of the time. This could include respiratory ailments, gastrointestinal problems, headaches, rheumatism, and even malaria. A visit to the doctor (if one was available) was a rare occurrence. So how did the early Upper Canadian pioneers deal with illness?

Through his contact with Montreal suppliers, Richmond merchant, George Lyon had access to traditional remedies such as spices from the Caribbean, as well as patent medicines and the most advanced new products from the large pharmaceutical companies of the day. A review of the suppliers’ invoices reveals a most interesting saga in the history of medical practices of the day.

From as early as 1820, George Lyon was purchasing spices from Montreal grocer Daniel Fisher. The pages of the Lyon Store’s invoice book show the purchase of cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger, cloves and allspice. From early times right into the twenty-first century, some spices have been used for cooking and/or food preservation. However, all of them had various medicinal properties that were used extensively by the early pioneers. (An explanation of their historical uses may be found on the UCLA website.)

While the total amount of each spice purchased varied, there are some surprising anomalies. Lyon purchased at least 4 lbs. of cinnamon, 1 lbs. of nutmeg, 13 lbs. of ginger, 1 lb. of cloves and 49 lbs. of allspice. Why was there only one small order for cloves and such a large amount of allspice?

In their investigation of spices in “Medicinal Plants” published in 1880, Robert Bentley and Henry Trimen stated that allspice could be used for the same purposes as cloves. If indeed this theory was widely accepted, the fact that cloves were far more expensive than allspice (six shillings a pound versus slightly more than one shilling a pound) could account for the preference.

From 1820 to 1825 Lyon bought various patent medicines from Hedge & Lyman of Montreal. This firm had evolved from the drug company begun by Lewis Lyman in 1800 and was later to become a major Canadian pharmaceutical company. As with everything purchased by Lyon, we don’t know which products were for his own use, which were special orders, and which were for the shelves of his store.

The names of many of the products are familiar to our ears. Castor oil, brimstone, “chamomile flourses”, Epsom salts, honey, root of liquorice, smelling salts and vinegar are some examples. Some, like alum, have a variety of uses. Did he buy it for its medicinal purposes or to use in dying and tanning?

Many of the most interesting remedies are either products that are no longer commonly found in modern homes, or “patent medicines”. The exact reasons settlers purchased many of these products remains a mystery as any one could have been used for a variety of different complaints.

In the early years, Lyon acquired some interesting liniments and soaps. Essence (of) Peppermint was a common product rubbed on temples to relieve headaches, on chests to relieve respiratory issues, and on muscles to relieve general pain. Opodeldoc was a soap liniment that was just being introduced into Upper Canada but continued to be widely used throughout the nineteenth century. It was rubbed on the the abdomens of babies to relieve bowel problems and for the general relief of joint and muscle pain in adults. The exact recipes used first by Hedge & Lyman and later by Joseph Beckett are unknown. Dr. Douglas McCalla in his investigation of mid-19th century Ontario general stores provides this recipe.

“Best brandy 1qt.; warm it and add gum camphor 1 oz.; sal ammoniac (ammonium chloride) and oil of wormwood, of each ½ oz.; when the oils are dissolved by the aid of heat, add soft soap 6 oz.”

Another favourite product was Windsor Soap, a brown soap manufactured in Windsor, England. It contained lavender, bergamot (lemonlike), caraway, petitgrain (distilled orange leaves), cinnamon & cloves. A far cry from the traditional homemade soap.

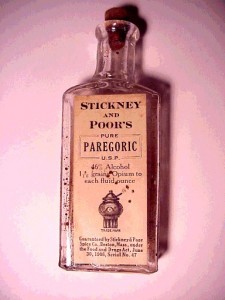

There were several different remedies used for gastrointestinal problems. Glauber Salts (sodium sulphate) and Seidlitz Powder, a mild laxative (a combination of tartaric acid, Rochelle Salt and sodium bicarbonate), were two such remedies. Paregoric Elixir was another which, despite its alcoholic and opiate ingredients, was given to children. An analysis from the Princeton University website notes that Paregoric was “… used to control diarrhea in adults and children, an expectorant and cough medicine, calm fretful children, and to rub on the gums to counteract the pain from teething.” The website quotes a formula taken from an 1870 publication:

“Best opium 1/2 dr., dissolve it in about 2 tablespoons of boiling water; then add benzoic acid 1/2 dr.; oil of anise 1/2 a fluid dr.; clarified honey 1 oz.; camphor gum 1 scruple; alcohol, 76 percent, 11 fluid ozs.; distilled water 4-1/2 fluid ozs; macerate, (keep warm,) for two weeks. Dose – For children, 5 to 20 drops; Adults, 1 to 2 teaspoons.”

With all that opium and alcohol, the patient could be both doped and drunk at the same time!

Some products were specifically refined for babies. Arrow root, Patent Groats (oat flour), and Patent Barley (used to make barley water) are a few examples. These could also be used by adults requiring easily digestible food. Embden Groats were crushed oats used to make gruel for the ill.

Cold remedies were common. Chinger Lozenges were available for sore throats. Anderson (Cough) Drops was one remedy for coughs. The drops were advertised in the “Montreal Herald” as “… the most Valuable Medicine ever prepared for Coughs and Consumption”. Testimonies claimed near miraculous cures. A very bad cold might require Syrup of Squills made from a combination of the bulb of the sea onion plant and two opiates – paregoric (described above) and laudanum (a stronger opiate).

Elixirs were popular and British Oil, a patent medicine with a base of mineral turpentine, was a regular import.

12 Rue St. Paul

Montreal 1825

Courtesy

Vieux Montreal

In the fall of 1824, Lyon tried a new supplier, Joseph Beckett & Co. Apothecarists and Chemists, who from late 1825 onwards, became his exclusive supplier. Beckett had recently opened a new store at the corner of what is now Rue St. Paul and Rue St. Laurent in the heart of the Montreal commercial district. During the 1820’s Beckett’s advertisements boasted of providing, “… secret remedies, drugs, specialized surgical instruments, medical textbooks and patent medicines”.

In July of 1827, Lyon made a larger than usual order of 29 different products. This was more than twice the size of a regular order. Included on the list were many of the remedies previously mentioned but also some new and unusual items. These included “Thomas’ Practice of Physic” which was probably the medical book, “The Modern Practice of Physic”, by Robert Thomas published in 1802. The descriptor of the volume states that the book “… points out the Characters, Causes, Symptoms, Prognostic, Morbid Appearances, and improved Method of Treating the Diseases of All Climates”.

The question is why was more than £1 spent on a medical book at this time? Unlike many other early settlements, Richmond had been fortunate to have some medical expertise available from as early as 1819. Maria Hill was famous for having assisted the wounded on the battlefield during the War of 1812. Assistant Surgeon, Christopher Collis of the 6th Regiment, was among the first settlers. Harry Walker in Carleton Saga, tells us that Dr. Collis was the first of the Richmond leaders to die but we have no exact date for his death. In December of 1825, George Lyon sent a note to Dr. A.J. Christie asking that he come to Richmond at once. Was there any connection between the death of Collis, the need for a doctor in December 1825, and the large order to Beckett & Co in July of 1827 that included a medical book? Further research will hopefully answer that question.

Key on the list of George Lyon’s purchases from Beckett was quinine. Surrounded by swamps, Richmond was as susceptible to malaria as the other areas along the Rideau. With the ramping up of construction of the Rideau Canal, it is not surprising to see Lyon purchasing the two most common remedies for malaria – Peruvian Bark and Quinine. Peruvian Bark was the bark from the cinchona tree, native to Peru. This remedy had been introduced to Europe in the 17th century and was known to reduce fever and pain. Two pounds of the bark cost Lyon 8 shillings. Far more expensive – but more potent – was Quinine which scientists had isolated from the bark and named in 1820. Its introduction into the community put the settlement at the leading edge of new European discoveries. The price (a quarter ounce of quinine cost more than 12 shillings) was probably prohibitive to most settlers. However, the price was on the decline as seen by the purchase of ½ oz. in August of 1828 for a little more than 17 shillings – a decrease of 30% in a year.

Thus George Lyon’s invoices show that a Richmond resident with access to enough funds was able to purchase a wide variety of traditional remedies, patent medicines and the most advanced new products.

SOURCES:

There are many internet sources (including Wikipedia) which provide excellent descriptions and explanations of the uses of most of the remedies discussed. The following list is provided as a guide to those resources we found to be particularly usefully.

- Account Book of George Lyon’s Store. City of Ottawa Archives.

- Bentley, Robert & Henry Trimen Medicinal Plants 1880. Online http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/33542#/summary

- “Benjamin Lyman”. Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?&id_nbr=5108

- Cox, Nancy & Karin Dannehi. Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities 1550-1820. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/source.aspx?pubid=739

- “Joseph Beckett & Company en 1825”. http://www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca/inventaire/fiches/fiche_gro.php?id=243

- McCalla, Douglas. “A World Without Chocolate: Grocery purchases at some Upper Canadian Country Stores 1808-1861.” Agricultural History vol. 79, no. 2 Spring 2005.

- “Medicinal Spices Exhibit” UCLA Biomedical Library: History & Special Collections. Online http://unitproj.library.ucla.edu/biomed/spice/index.cfm?spicefilename=SpicesAsMeds.txt&itemsuppress=yes&displayswitch=0

- “Paregoric”. Princeton University. Online http://www.princeton.edu/~achaney/tmve/wiki100k/docs/Paregoric.html

- Thomas, Robert. The Modern Practice of Physic. Vol. 2 . London: 1802 online (Google eBook) http://books.google.ca/books/about/The_Modern_Practice_of_Physic.html?id=YUsUAAAAQAAJ

- Walker, Harry & Olive. Carleton Saga. Ottawa: 1968 Carleton County Council.

- Welch, Edwin. “A Pioneer Store in Upper Canada” Ottawa:1982. Unpublished manuscript written for The Historical Society of Ottawa. City of Ottawa Archives, A2009-0137 Box #2, # 34 D 04, ABUS 19.